General Discussion Forum home - Go back to General discussion

|

Electrifying Sydney

|

|

« Back ·

1 ·

Next »

|

|

|

|

Location: Sydney, NSW

Member since 28 January 2011

Member #: 823

Postcount: 6911

|

From time to time, in discussion of early radio sets, there's mention of the electrification of Australian houses. What follows is an extract from “Electrifying Sydney -- 100 Years of Energy Australia”, by George Wilkenfeld and Peter Spearritt (2004).

Those of us who grew up in Sydney may well recall the campaigns to Live Better Electrically, and the numerous TV cooking shows featuring electric ovens. This article explains how the electricity provider decided to take on gas with a vengeance and electrify Sydney's homes.

Note also that one of the early household drivers of electricity over gas was the radio.

(SMH = Sydney Morning Herald)

Electrifying the Home

Electric light took the world by storm. Cities and towns all over the globe were lit by electricity between the 1880s and the l920s. Suddenly light could be created by the flick of a switch, without the smell, flickering or fire risk associated with gas or kerosene. In the workplace and the home, electric light lengthened the day for activities that required strong and steady illumination, from reading and sewing to carpentry and watchmaking.

The incandescent mantle had maintained the popularity of gas for home lighting through the 1900s and 1910s, and the Sydney Municipal Council’s difficulties in getting new plant during World War I kept gaslight alive for a few more years, but it gradually gave way to electric lighting from the early 1920s. All over Sydney, houses had their gaslight pipes converted to electric wiring conduits. By the late l920s electricity had replaced gaslight in over two thirds of Sydney’s homes and new homes built in this speculative decade were all wired for electric lighting. In a society where most girls learned to knit and sew and most boys took up some male hobby, electric light helped in countless ways. Even cooking became easier in kitchens lit by electricity.

Although electricity had a natural advantage for light and power, gas had a natural advantage for heat. The technology was simple - all you had to do was burn it. The Australian Gas Light Company, having lost the battle for home lighting, fought to build and hold the market for heat.

In Sydney’s mild climate, the cooker was the hearth of the home. Gas cookers had been locally manufactured since the 1880s, were cheap to purchase and run, and often installed free of charge by the gas companies. Gas cookery demonstrations began at the new Haymarket showroom in 1893, and continued in one form or other until 2003.

Mrs Harriet Wicken, lecturer in domestic economy at the Sydney Technical College, declared in her Kingswood Cookery Book in 1891 that ‘Cooking by gas is far superior, cheaper, and cleaner than cooking by any other means. The gas is always ready for use day and night at a moment's notice. Its use for cooking purposes renders the Mistress of the house almost independent of servants’. By the mid 1920s AGL (Australia Gas Light Company) had showrooms in the City, Parramatta, Burwood, Waverley and Rose Bay, gas cooking demonstrations and tri-weekly radio broadcasts. It persevered with an advertising campaign en titled ‘The All-Gas Home’, which showed just how many appliances could be run by gas, from cookers and coppers to room heaters and bath heaters.

By the late twenties Sydney’s 250,000 households had a huge investment in all manner of gas cooking appliances, from grand stoves and ‘Early Kookas’ to the simple gas ring. Gas was quick and relatively cheap and generations of cooks – housewives and domestic servants – were not only used to it, they relied on it.

Apart from cooking, hot water was needed for laundry and bathing, and the living room, at least, needed heating in winter. Central water heaters were still rare, but many middle class households installed small gas water heaters in the bathroom and above the kitchen sink Laundry day (usually Monday) was hard work for women, and any means to make it easier found eager takers. Most better-off households soon gave up cutting Electrifying Work place and Home wood and lighting a fire under the laundry ‘copper’, opting for a gas copper instead. In poorer households laundry water and bath water continued to be heated in the kitchen – although increasingly on a gas rather than wood stove - and ferried out in saucepans or pots to the ‘laundry’, often a cement tub in a lean-to at the back of the house. On bathing days the hip bath also stood in the kitchen. Running hot water remained a luxury that many Sydneysiders had to do without, even after World War II.

Electricity versus Gas

AGL’s ‘all-gas home’ campaign promised a wide range of household appliances – even absorption type refrigerators – but there were some new products that gas simply couldn’t power. The radio was the first, and in many ways, still the most dramatic of these. Suddenly up to date news and an extraordinary variety of entertainment – from popular and classical music to serials and, of course, advertising – we re available in the home. First introduced in l923, radios were to be found in over one fifth of Australian homes by l930, and nearly two thirds by 1938, a dispersion rate far quicker than the telephone.

While Sydneysiders reveled in the new possibilities for electric-powered home entertainment, with the radio and later th e record player or ‘gramophone’, they were slow to buy other electric appliances and even slower to replace their familiar gas appliances with electric ones. Apart from lamps, the only electric appliance to be found in most households in the 1920s was the iron, which was not a large energy user. Just as the mass connection of lower-income consumers had driven down average household gas consumption in the 1870s, it drove down average electricity consumption in the 1910s and 1920s. The resulting under-utilisation of vast capital resources became a pressing concern. In 1922 City Electrical Engineer, H.R.Forbes Mackay, addressing the Electrical Employers’ Association of NSW, complained of ‘thousands upon thousands’ of lighting consumers, whose annual consumption amounted to only 70-140 kWh . He noted that the Council was legally compelled to supply these consumers, yet the revenue received was barely enough to cover generating costs, let alone capital charges. In hi s opinion, the best way of meeting the situation was to organise a campaign to introduce more electrical devices into the home.

The Council embarked on the direct promotion, sale, hire and repair of electrical appliances in the late 1920s, and continued this strategy without interruption for the next 60 years. Another part of the strategy to in crease sales was the tariff structure adopted in mid 1925, under which the need for separate light and power meters for households was abandoned, typical domestic accounts were halved and the marginal cost of electricity reduced by up to 75 per cent.

A Sales Branch was created in 1926 ‘to increase the sale of electricity by means of selling appliances’. Demonstration trucks toured the suburbs to not only sell appliances but to install them, repair them and fit new wiring if necessary. Salesmen were told to attempt to get their housewife ‘targets’ to invite them into the kitchen. Even if an all electric kitchen didn’t eventuate, at least some power points might be installed.

By l930, when it was clear that the Wall Street crash had sparked a world wide depression that would last for some years, th e electrical retailers complained about the Electrifying Work place and Home competition from the Council’s retail operations , and the Council withdrew from direct selling of appliances. In 1936 the Sydney Council County resumed appliance sales, but agreed to sell only larger items such as cookers and water heaters, and leave radios, irons, vacuum cleaners, toasters, sewing machines and other smaller appliances to electrical retailers.

The best way to increase residential electricity demand was to capture the thermal uses which householders still associated with gas, and the most obvious place to start was cooking. As well as the promotional methods of AGL, the Council also had the example of the pioneer of electric cooking promotion in Sydney, the St George County Council, which had started public demonstrations of electric cooking in 1927 in its Kogarah showroom and at the stores of electric appliance retailers in the district.

In 1934 the Sydney Municipal Council launched its campaign by offering to contribute £6 for the connection of the first 5,000 cookers purchased and started twice weekly cooking demonstrations at its showrooms in Druitt Street. In June 1935 it began holding regular cooking demonstrations in public ha lls and cinemas. Audiences of up to 2,000 (invited by leafleting the district) were treated to musical items interspersed with talks about the uses of electricity, and practical demonstrations on electric ranges installed on the stage.

The glamorous Art Deco appliance showroom in the renovated QVB, opened in December 1935, included a ‘model kitchen’, along with model living-room, bedroom and laundry. The display windows promoted the latest electric cookers and the model kitchen inside was a permanent base for the cookery demonstrations which were to become a Sydney County Council (SCC) trademark. The zeal of the promotion at first caused concern even to the councillors. In April 1936 they disapproved of the display of a new electric cooker alongside a 1911 gas stove as ‘unethical’ (SMH 22.4.36).

In the 1930s the market for large electrical appliances was still relatively modest, and the Council continued to play a vital promotional and retailing role. It sold nearly nine in ten of all the new cookers connected to its supply in 1938, and in 1939, noted that ‘Electric ranges are now common and accepted household equipment and no special inducements are necessary to ensure their extensive use’. Nevertheless, the promotional cooking tariff introduced in 1933 remained as late as 1968.

At the end of 1939 the Council began a ‘co-operative merchandising plan’ with refrigerator manufacturers, offering a five year hire purchase scheme. The war put an end to most special deals, but this hardly slowed the growth in sales. The efforts of the Electricity Sales Branch were credited with fully 45 per cent of the total increase in the Council’s electricity sale s between 1935 and 1946 – 14 per cent through equipment sales, 4 per cent through hiring and 27 per cent through advisory services.

By 1951 there were regional showrooms at Bondi, Burwood, Crows Nest and Campsie, replicating in miniature the facilities at the QVB. At these showrooms customers could pay their accounts, get advice, shop for appliances and attend regular cookery demonstrations in a small auditorium, where they could also view films such as Yours to Command and Your Career in Electricity (1969). In 1951 about 15,000 customers, mostly women, attended cooking demonstrations. In the 1960s annual attendances stabilised at around 21,000, but rose again in the early 1970s to about 27,000. Electric Electrifying Work place and Home cooking was no longer unfamiliar (indeed by the mid sixties more Sydney households cooked with electricity than gas), but customers liked the recipes and the sociability, and there were still new things to learn. In 1973 the Council produced a colour film The Kitchen Goes Metric, and the advent of the microwave oven in 1980s caused another surge of interest.

The friendly voices and faces of its home economists carried the Council’s message into virtually every communications medium: radio (from 1936), television (1956), and video (1978). Cookery News , first mailed out with electricity bills in 1953, was replaced in 1976 by Watt’s News , which carried not only recipes but information on promotions, electrical safety, new appliances and new ways to use (and eventually, to save) electricity.

Showroom cooking demonstrations ended in 2002 with the closing of the Chatswood showroom, but Energy Australia still employed a home economist in 2004 to deal with requests for advice by mail, telephone or email. She gave advice on adapting recipes from conventional to fan-forced electric and microwave ovens, just as Mrs Whiffen had advised on adapting recipes from wood fires to gas cookers over a century earlier. The fact that Energy Australia now sold gas made it possible to give advice on the best use of gas cookers as well.

Although the Council needed electric cooking to underpin the economics of supply, the real appeal of the all-electric home for the consumer of the 1930s revolved around the enormous range of appliances that either de pended on electricity for their very existence – including the radio – or that replaced manual power and dexterity, most notably the washing machine, with its electrically-powered mangle, and the sewing machine. Floor polishers and vacuum cleaners replaced hands and knees, at least in the advertising images of upright housewives whisking about their daily tasks. Such appliances were almost unknown in all but the better off households until the l950s, but they were regularly advertised in women’s magazines from the l920s.

By the end of the l930s most households had at least a toaster, an iron and a radio, made in one of the new factories in Sydney or Melbourne. The spread of larger electric appliances awaited the consumer revolution following World War II, but in the meantime electricity continued to eat into the gas market. Electric room heating became sufficiently common so that in the post war period radiator use placed particular stress on the supply system during the frequent periods of coal shortage, and so was generally prohibited. There was also steady growth in permanent off peak demand with the increasing penetration of night rate storage water heaters, the Council’s largest selling appliance line in the late 1940s.

The Council’s promotional zeal continued through the war years, despite frequent appeals to the public to put the war first. It planned for the ‘complete electrification’ of post-war homes. Aggressive promotion continued through the supply problems of the late l940s when coal strikes regularly interrupted supply. In August l950 the Chairman of the Electricity Commission of NSW, H.G.Conde, criticised the advertising campaigns of the SCC and other electricity suppliers, telling them that they had a ‘moral obligation’ to put ‘the soft pedal on sale s promotion’ because of the shortage of generating plant to supply ordinary needs.(SMH 3.8.1950) But the SCC continued to distort its pricing and promotion in favour of residential consumers, providing a pro- Electrifying Work place and Home consumer underpinning of the long boom that started in the early l950s and saw almost every household in Sydney with a refrigerator by the end of that decade.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Administrator

Location: Naremburn, NSW

Member since 15 November 2005

Member #: 1

Postcount: 7590

|

Live Better Electrically

Yep, from the Sydney County Council and the neighbouring Prospect County Council used to sponsor the Sunday footy calls on 2UE around the same period. AGL (The Australian Gas Light Company) competed quite fiercely with these campaigned with the "Natural Gas, the living flame" ads with the dancers in glue tights mimicking a burner on a stove. It was during the transition from coal gas to natural gas.

AGL has little to do with gas manufacture or distribution these days and is far more involved with generating electricity - a climax of the evolution that started at the time radio came into our homes.

The big problem with gas, aside from the obviously difficulty in running a radio from it, is that if an appliance is not maintained then the combustion process will give off carbon monoxide and the flame must be kept blue to stop this happening. Flues on the old bathroom water heaters also had to be swept to ensure no CO build-up.

I remember my parents paying their electric bill at the Burwood showrooms which were just up the road from the Telecom Business Office, where the phone bill would be paid. There was an AGL Gas Centre across the road though we never 'had the gas on'. All the bills get paid on the humble laptop now and those centres are long gone, replaced with $2 shops.

‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾

A valve a day keeps the transistor away...

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Sydney, NSW

Member since 28 January 2011

Member #: 823

Postcount: 6911

|

I also recall the House Power Plus campaign of the 1960s, aimed at getting more power points installed in new houses. It's probably around then that the double GPO became a popular standard installation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Sydney, NSW

Member since 28 January 2011

Member #: 823

Postcount: 6911

|

Also from that book:

"The last DC supply [in Sydney] was ceremonially switched off on 28 August 1985 at a function to mark the 50th anniversary of the first meeting of the Sydney County Council"

Wonder who that last DC customer was?

|

|

|

|

|

|

Administrator

Location: Naremburn, NSW

Member since 15 November 2005

Member #: 1

Postcount: 7590

|

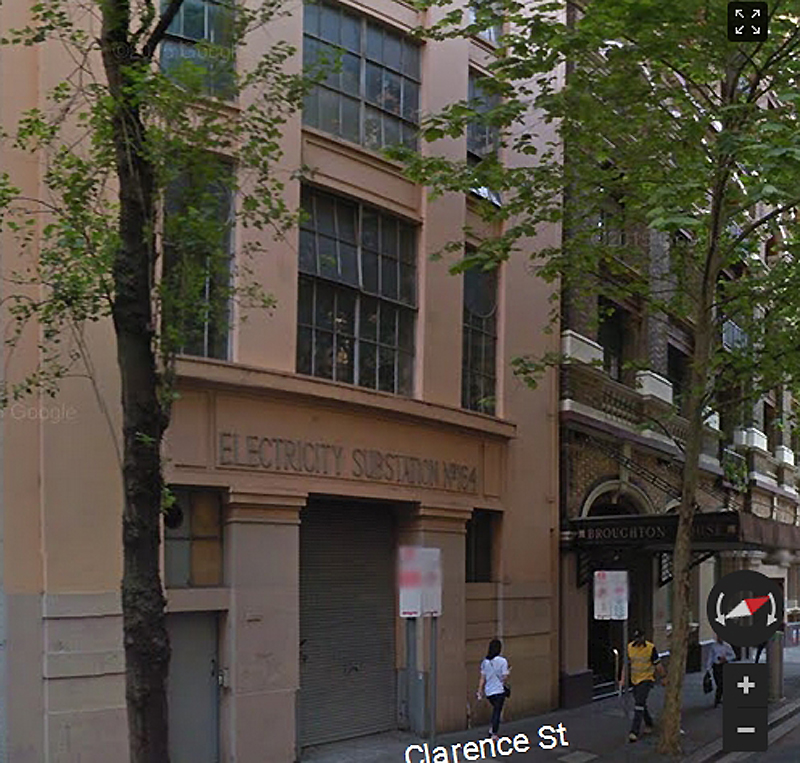

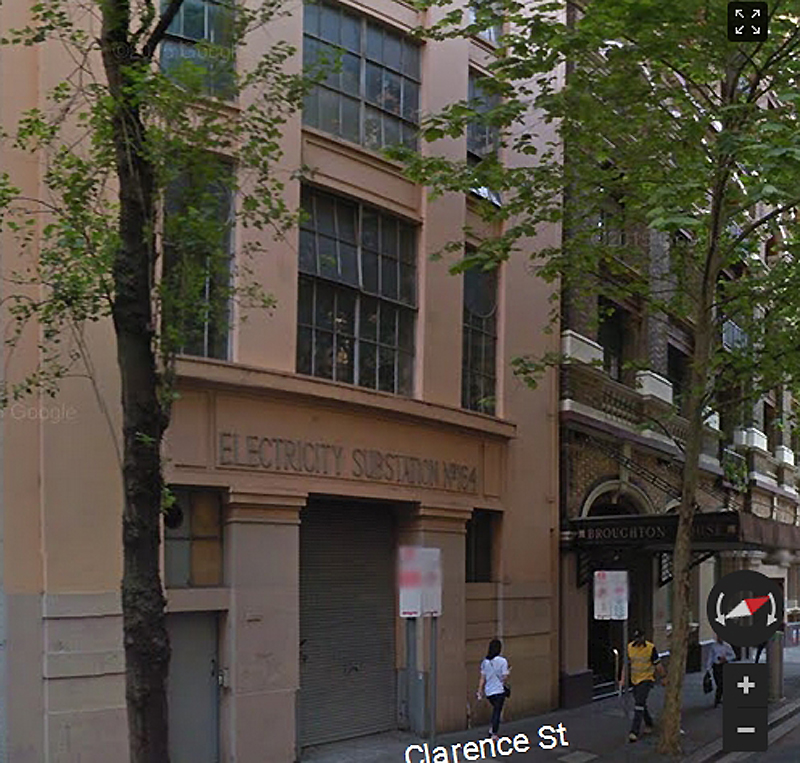

Electronics Australia covered that event. I am sure it is the substation in Clarence Street. The last customers would be buildings that still contained original equipment on their lifts and escalators. Whilst the universal motors used on lift machines would happily run on AC there wasn't an easy way to control ramp up and ramp down for AC, whereas all lift control now is AC with modern variable frequency drives. So DC with stepped relays and huge bleed resistors was the norm and in a CBD like Sydney with so many ancient buildings it was just cheaper to run DC mains alongside the AC ones.

‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾

A valve a day keeps the transistor away...

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Sydney, NSW

Member since 28 January 2011

Member #: 823

Postcount: 6911

|

"The last Sydney County Council customer to receive direct current was Australia Post at the GPO."

http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/mob/collection/database/?irn=164573&search=28&images=&wloc=&c=1&s=86

"Substation No 164 [183 Clarence Street] is [was] the last remaining direct current substation from the original DC network which supplied power to central Sydney."

"The original city power supply was direct current and was fed to, ultimately, 6 major DC substations in the central business district. These included Town Hall Substation (No 1 built 1904), Lang Park Substation (No 2 built 1904), Phillip Street Substation (No 3 built 1913), Castlereagh Street Substation (No 82 built 1914), Clarence Street Substation (No 164 built 1926) and Dalley Street (No 263 built 1929). These substations all contained large rotary converters which converted the DC power from the power stations to alternating current (AC) for supply to distribution substations.

In some cases, customers were supplied with DC power directly, although this tended to be limited to larger industrial operations or for lifts in inner city buildings. By 1930, the MCS had decided to convert to exclusively AC power for cost reasons, a process which was not completed until 1958. Of the DC substations, only one survives. The Clarence Street Substation has had its equipment completely removed and is earmarked for the housing of a future Zone Substation. It presently houses a small AC distribution substation in one corner of the building. The Dalley Street Substation was completely rebuilt in the 1960s on the site of the original substation and is now [was] used as an AC 132kV Zone Substation."

http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=3430540

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Silver City WI, US

Member since 10 May 2013

Member #: 1340

Postcount: 977

|

I wonder why gas stoves are not required to be vented? Is it because they were always made this way from back in more naive times and the tradition continues? What if someone was cooking most of the day, that's a lot of BTUs/CO!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Administrator

Location: Naremburn, NSW

Member since 15 November 2005

Member #: 1

Postcount: 7590

|

Old houses had air vents in most rooms though especially in the three wet areas of the home. It is a popular belief that carbon monoxide is heavier than air but it is not. Carbon monoxide is lighter than air so it would have easily been vented, providing the vents weren't choked up with dust though again it came back to good maintenance. An orange flame from a town gas supply was, and still is, bad news. Unfortunately not everyone is aware of it.

In homes that were fitted with gasoliers there were vents in the ceilings that were known as ceiling roses. This name carried over to the electrical ceiling rose that one can fit a hanging light fitting from when it is just suspended by the cable. The original plaster ceiling roses allowed carbon monoxide to escape.

‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾‾

A valve a day keeps the transistor away...

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Silver City WI, US

Member since 10 May 2013

Member #: 1340

Postcount: 977

|

Interesting about the roses, have seen fake round mouldings you can buy today, will look for real legacy examples in old buildings. A yellow gas flame may indicate air mixture not sufficiently opened or you already have depleted oxygen in room?

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Albury, NSW

Member since 1 May 2016

Member #: 1919

Postcount: 2048

|

There is a great Documentary relating to this topic , I watched it last week and thought it was great ,Its called Hidden Killers of a Edwardian Home ,,,,, Things like a Electric table cloth !!!hah anyway you may like to look at it so heres a link.

https://youtu.be/i7kxUyvkXjw

|

|

|

|

|

|

Location: Sydney, NSW

Member since 28 January 2011

Member #: 823

Postcount: 6911

|

|

|

|

|

« Back ·

1 ·

Next »

|

|

You need to be a member to post comments on this forum.

|

|

|